Money laundering doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It always has a backstory — fraud, corruption, trafficking, crimes tied to environment or social harms. The EU, in its characteristic thoroughness, has explicitly listed 1 several environmental, social, and governance (ESG) violations as predicate offences to money laundering. This pulls anti-money laundering (AML) and ESG agendas together, which puts leaders in either field on a shared compliance timeline culminating midway 20272.

Two regulatory tides are converging on European firms. On one side: the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) combined with the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CS3D), which force companies to disclose ESG impact and take responsibility on value chain risks. On the other: the EU’s new AML package (AMLR, AMLA, AMLD6), which harmonizes the rules against illicit money flows. Increasingly, experts expect ESG and AML enforcement to move in tandem.3

Image: the earth as a warn out ball subject to the tides

Political debates may slow the roll-out of CSRD and CS3D4, but the climate itself shows no signs of easing the pressure on us humans5. 2025 has already offered some reminders of what’s at stake. Public, academic and investor scrutiny6 ensures ESG urgency will not cool down, despite parliamentary timetables.

For executives, the hard question is not “why” but “how”: how do I grasp risks through a products’ value chain, and where do I start? For complex goods the challenge is obvious, but simpler products, like furniture, can be caught up in forced labour, illegal logging, sanctions breaches and corruption scandals.

If you are a business with thousands of suppliers, or a Financial Institution (FI) with millions of customers, applying a realistic risk-based approach is critical. After all, crisis events like negative publicity or even shareholder meeting disruptions may be on the table. Especially for FI’s finalizing AML transformation- and remediation programs, diving straight back into another is not appetizing.

Inspired by the CS3D requirements on value-chain ESG due diligence, this article introduces a data-driven, open-source methodology that links ESG and AML into a single, explainable framework, tracing and measuring risks through the value chain. This approach focuses on the financial industry, but can equally be tailored across economic sectors.

Why ESG and AML converge in supply chains

While the EU CSRD directive has opened the world to increased ESG reporting, the CS3D is where the rubber will really meet the road for sustainability responsibility7 . Its requirements for firms to execute ESG due diligence in their entire value chain has far-reaching consequences. In the AML field8, practitioners are more used to such a level of scrutiny. Financial Institutions (FIs) and other gatekeepers to the financial system already require an understanding of their customers’ business practises to safeguard against AML risks. However, even FIs tend to be unable to look much further than their direct business relations (customers or suppliers).

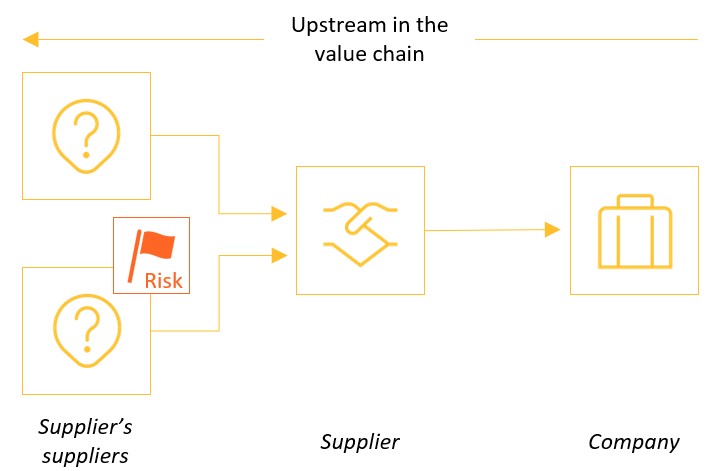

To make matters complex, ESG and AML risks both often originate upstream in a supply chain in places like: raw material mines, agricultural fields, or industrial hubs where labour abuses, environmental damage, and illicit money flows may arise9. Especially in the context of the CS3D, companies become liable for their upstream risks (i.e. your supplier’s suppliers – see adjacent for visualization).

If you are a financial firm providing funding and governed within AML regulations, these value-chain risks include your customers10. And thus, through its customers, an FI is exposed11 to risks such as:

- Labour exploitation: in mining, agriculture, or manufacturing: simultaneously an ESG concern and a generator of illicit profits.

- Illegal environmental practices: such as logging, rainforest mining, or illegal waste disposal: ESG harms that are often tied to trade-based money laundering.

- Corruption and sanctions evasion: governance failures that drive both ESG degradation and AML risk.

A solution to the lack of value chain transparency is to understand the origins of a product. By tracing products back to raw- and intermediate materials, and then mapping those materials to place-based risks, companies gain a risk-based view that speaks to both sustainability concerns and financial-crime vulnerabilities. In the remainder of this article, we will explore this in an AI-driven approach.

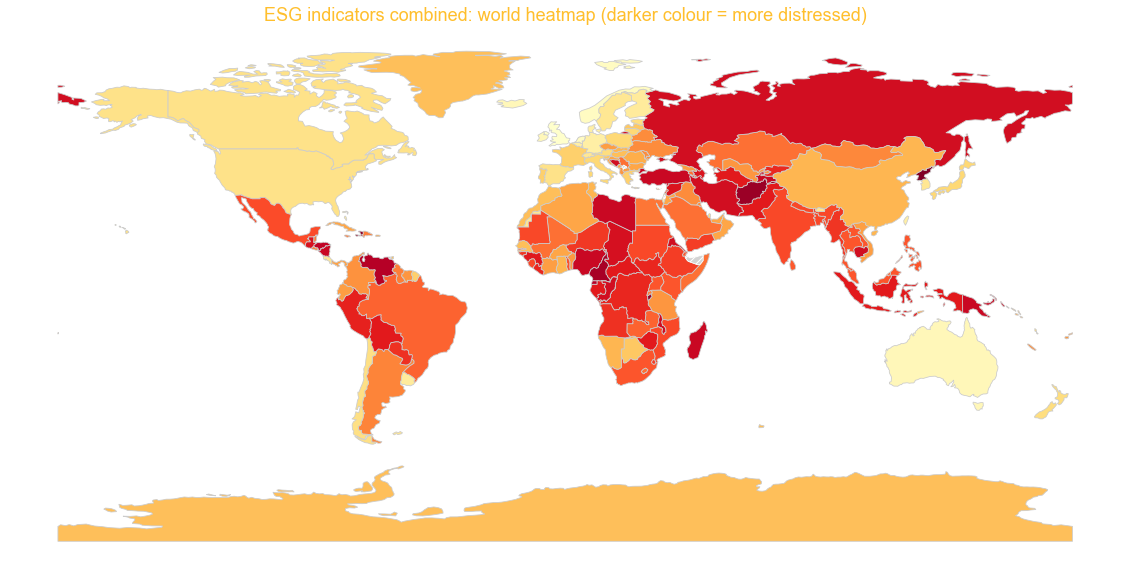

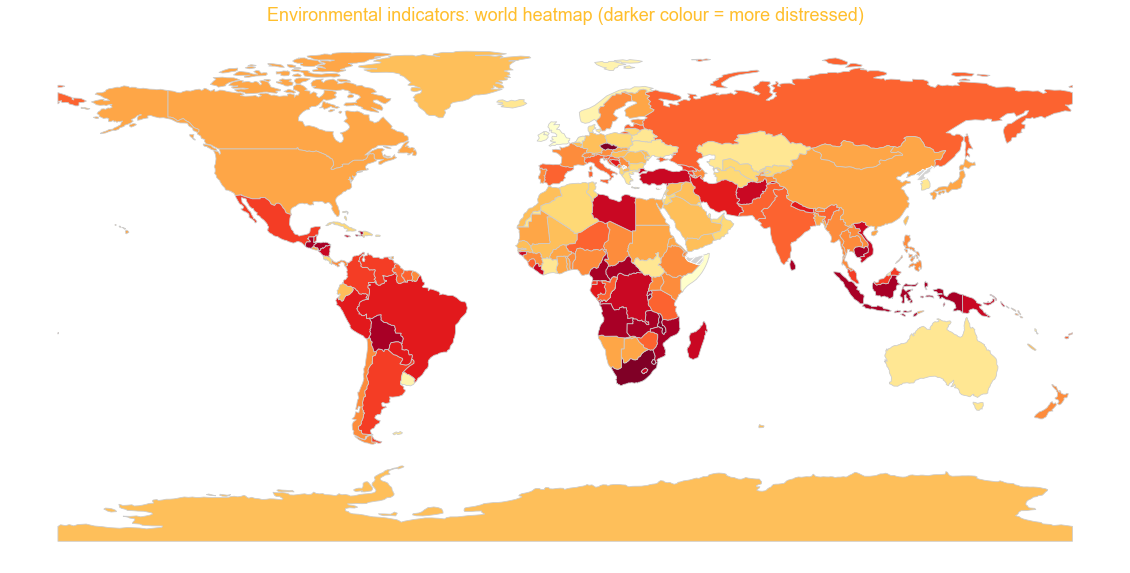

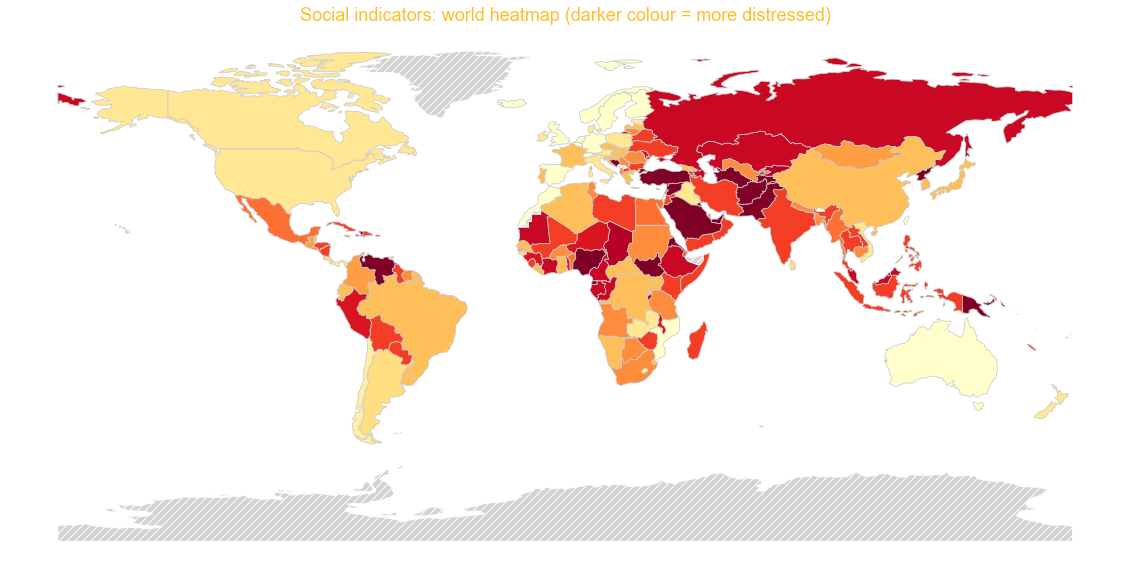

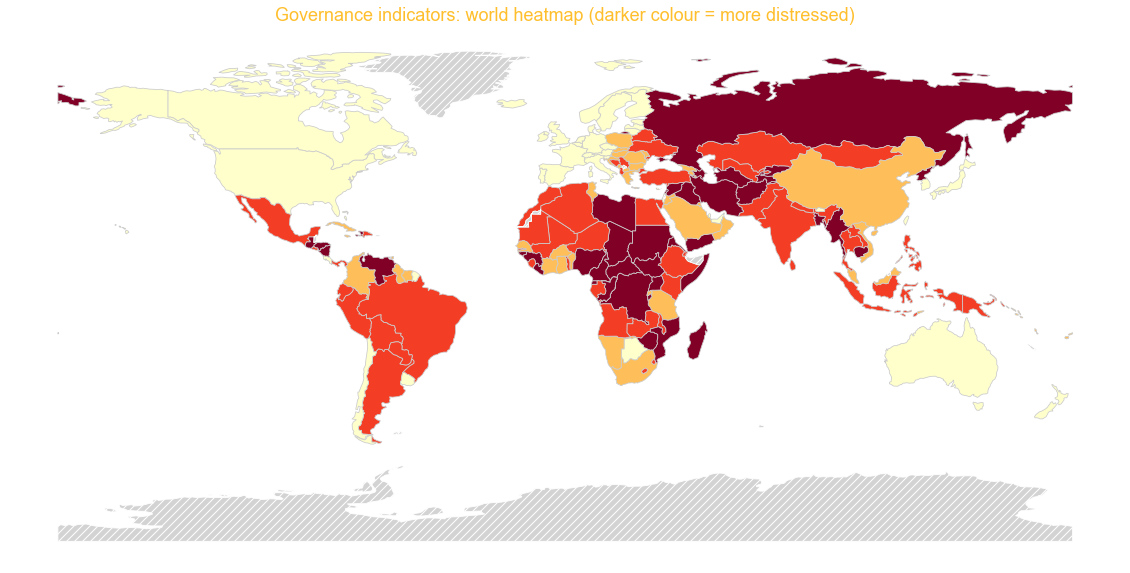

Step 1: build a global ESG heatmap

Our foundation entails an extensive dataset of ESG indicators for the planet. AML practitioners should be familiar with this approach, as risk lists are a staple of AML efforts12. While the EU CSRD details many potential disclosure requirements at a company level13, many of these cannot be estimated on a country level. So, we need higher-level indicators to understand ESG risks per geographic area. There are various sources which can be consulted for this:

- Labour indicators: ILO statistics on child labour, Global Slavery Index, prevalence of informal work, statistics on workplace safety.

- Environmental indicators: satellite-derived vegetation loss, water stress indices, air quality records, etc.

- Governance indicators: corruption perception scores, conflict-mineral registers, NGO reporting on extraction, sanctions exposure

For this analysis, we created a dataset which combines a number of these sources into harmonized overviews. The procedures to create this dataset are open sourced on our GitHub page. Visualized on the world map, the various indicators we collected on Environmental-, Social-, and Governance risks look like this:

Step 2: connect materials to origin geographies

Raw materials rarely come from a single source. Copper may originate in Chile, Zambia or China; palm oil in Indonesia or Malaysia. Each carries different ESG and AML risk footprints.

This step builds up a material library, and overlays the material library with sourcing probabilities. We draw on mining production statistics, industry reports14, and statistics of agricultural production15. The result is a sourcing world map: estimates from combined production sources for all mayor product input materials on a global level.

Illustration: Let’s use a lighthearted example to illustrate our process: Biodegradable glitter cosmetics. It even has ‘biodegradable’ in its name!

A key component (the glitter) in such products tends to be Mica, approximately 21% of which is mined in Finland which faces relatively few ESG risks (predominantly environmental risks). However, a combined 20% is mined in Madagascar, Turkey and India, countries facing relatively more ESG risks16 (for instance: risks of poor worker protection and artisanal mining17).

Step 3: use AI to identify likely core materials in an end product

At this point, the challenge is to break down an end product into its raw and intermediate materials. To do this, we can leverage an AI solution that is trained to reference the materials contained in the datasets built in steps 1 and 2. Using a local AI solution for this task18 ensures we keep our input data private, something online AI options have struggled with. Furthermore, a local solution allows us to make AI output more tailored through training.

Fortunately, Deepseek has released some lightweight reasoning models for public use, and is leveraged for this step19. Our AI model acts as an assistant to execute three steps:

- Read product and company descriptions

- Suggest a list of likely component materials in these end products

- Provide a percentage makeup of the use of component materials in the end product

Imaged: Our AI Deepseek model reasoning its way through the makeup of our ‘Biodegradable glitter cosmetics’ example20

Step 4: Understand holistic risk levels

With the material list from our AI output and sourcing map in hand, we can build a risk exposure profile for each end product, or combine a number of products to understand a business’s value-chain ESG risks. The value of this lies in explainability. A high-risk rating is no longer a professional judgement call; it is a chain of evidence with a defensible narrative for management, regulators, suppliers, and customers.

Illustration: Going back to our example of Biodegradable glitter cosmetics, we can use our AI model output combined with our ESG heatmap and sourcing probabilities to find the final ESG risk inherent in its value chain. The main ingredients21 are indicated below:

Note that this at-first-glance sustainable product carries ESG risks in its value chain. In this risk-based approach, Biodegradable glitter cosmetics fall into a medium ESG risk level22. Naturally, the final ESG risk should be determined by actual supplier- or customer due-dilligence23.

Our illustrative example turned out with an average ESG risk. Other products may fare worse, for instance if their value chains contain ingredients like Barite, Cobalt, Talc, Palm Oil, or various nut and seed oils.

Conclusion

The regulatory tide is clear: under CSRD, companies must report ESG impacts; under CS3D, they must act on them. Both demand supply-chain visibility that most companies currently lack. Add in a changing European AML context for environmental and social crimes, and the need for a unified, explainable risk understanding of your business’s customers and suppliers is urgent.

The value chain methodology described here provides exactly that. By linking open-source ESG and AML indicators to raw materials, mapping them to geography, and leveraging AI solutions, companies can present transparent, explainable risk assessments. This method could be automated for low-risk areas, and would require due-diligence for higher risk areas. For executives, the payoff is a credible foundation for EU ESG compliance risk analysis, and a defensible cause to initiate and prioritize supply chain due diligence on ESG risks.

Interested in discussing a risk-based approach for connecting ESG and AML in your organization’s value chain?

A note on limitations

As with all approaches leveraging open-source data and AI solutions, there are a number of limitations underlying the approach detailed in the article. Users of open source information need to be aware of timeliness thereof, as well as potential biases in the data presented. Additionally, using AI outputs go hand-in-hand with the acceptance of certain its design element, including whatever weights and probability scores are assigned to its outputs. In our approach here, we took steps to minimize both by rigorously limiting the AI models freedom both on interpreting input, and output creativity. These are not reasons to dismiss the method but rather guardrails for responsible use.

Footnotes

- As per: DIRECTIVE (EU) 2018/1673 ↩︎

- Both the various EU AML directives and the EU CS3D directive are, at time of writing, set to become active laws from July 2027 ↩︎

- For example, in: S. Visser, R.A. Regtering, 2023, “Ondernemen met oog voor mens, millieu en maatschappij: van nobel streven tot witwassen”, source here ↩︎

- While the ‘Omnibus’ proposal in the EU has delayed and changed the ESG agenda, there is no sign of stopping the codification of ESG regulation and voluntary control thereof by businesses ↩︎

- This article does not debate the desirability of ESG laws, or the negative contributions to global warming human activities have had over the past 100 years, and takes both of these as given. ↩︎

- For those looking for some discussions the impact of ESG on investments, CFA institute has an interesting collection here ↩︎

- Throughout this article, sustainability is used as a synonym for ESG so as not to bore the reader too much with abbreviations ↩︎

- Similarly, throughout this article, AML is taken to mean anti-money laundering, sanctions risks, and corruption risks to make the reading less tiresome ↩︎

- This becomes especially apparent when we consult the EU’s 2018 grouping of criminal activities (DIRECTIVE (EU) 2018/1673) in article 2, which can be the underlying offence to money laundering as described in article 3. In article 2, various ESG offences are noted which can result in money laundering offences. These include environmental crime, corruption, and human trafficking ↩︎

- Neve at all, 2024, “Dreigingsbeeld Milieucriminaliteit 2024”, source here ↩︎

- As noted in the introduction, ESG risks are not only legal in nature, they may also impact business reputation as indicated in recent coverage on deforestation risks and providing financial services to the oil-and-gas sector ↩︎

- And are also used by the European Banking Association in their 2025 Guidelines on management of ESG risks, e.g. on p19 ↩︎

- Roughly 1100, which require specification to company profile and relevance. More details here: https://business.gov.nl/sustainable-business/sustainable-business-operations/mandatory-csrd-what-does-it-mean-for-my-business-a-step-by-step-plan/ ↩︎

- Sourced mainly from the US Geological Survey statistics here: https://www.sciencebase.gov/catalog/item/65a6e45fd34e5af967a46749 ↩︎

- Predominantly sourced from the UN Food and Agriculture organization here: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QV ↩︎

- In the above world heatmap a continuous score from 1-4 is employed. Finland scores 1.4 out of 4 whereas India (2.9), Madagaskar (3.5) and Turkey (3.5) score higher on the ESG risk scale. ↩︎

- Further investigation indeed corroborates the potential risks of (estimated) artisanal mining for Mica, as reported here in the ASM database ↩︎

- In processes where output quality and consistency is crucial, leveraging AI in specific tasks rather than general tasks is in our opinion the current best course of usage. ↩︎

- The R1 distilled version using 8 billion parameters, as bench-marked here: https://llm-stats.com/models/deepseek-r1-distill-llama-8b ↩︎

- Command-prompt front-end featured here for illustrative purposes, as the back-end leveraged in our process does not feature GUI output ↩︎

- As estimated by the AI output, covering approximately 90% of ingredient makeup ↩︎

- To be exact, it ends up with a score of 2.3 on a continuous scale of 1 (least risk) through 4 (most risk) ↩︎

- Detailing ESG/AML customer due diligence processes for an FI is out of scope for this article, but would face challenges similar to analysing any other type of ‘predicate offence’ occurrence (e.g. underground banking, etc.) with its customers ↩︎